Engineering the Extraordinary: Steve’s Journey from Childhood Dream to Iconic Structures

Sometimes a single moment in childhood can shape an entire career.

For Steve Huey, that moment came in 1971 at age 11, standing outside the Air Force Academy Cadet Chapel in Colorado Springs. “When I walked out, I told anyone who would listen that someday, THIS is what I am going to do. I am going to design buildings like this,” he recalls. “I had no clue what an architect or an engineer was – it was just a kid’s pipe dream.”

That pipe dream became reality in the most extraordinary way possible. After 37 years in the industry, Steve, a Principal at Wallace Design Collective and co-founder of the Kansas City office, is preparing for retirement next year. However, not before completing work on the very building that inspired his career: the Air Force Academy Cadet Chapel itself, where he now serves as the Engineer-of-Record for the wall panels replacing the entire exterior of this iconic structure.

Building a Foundation

Steve’s professional journey began in earnest when he and Mike Gray started their own firm in 1988. After Wallace acquired the company in 1995, Steve found his home base for what would become a legendary career in facade engineering. His expertise began with schools, but a chance encounter would change everything.

“A client suggested her husband talk to me about a house he was building,” Steve remembers. “It was a copper cube, with a pyramidal roof, pierced by a cylinder off center with an observatory on top – your typical bachelor pad on a hill in the middle of nowhere.” That husband was Bill Zahner, and their collaboration on figuring out how to build a curved beam from plywood and studs supported by three telephone poles sparked a partnership that would define both of their careers.

A Philosophy Born from Necessity

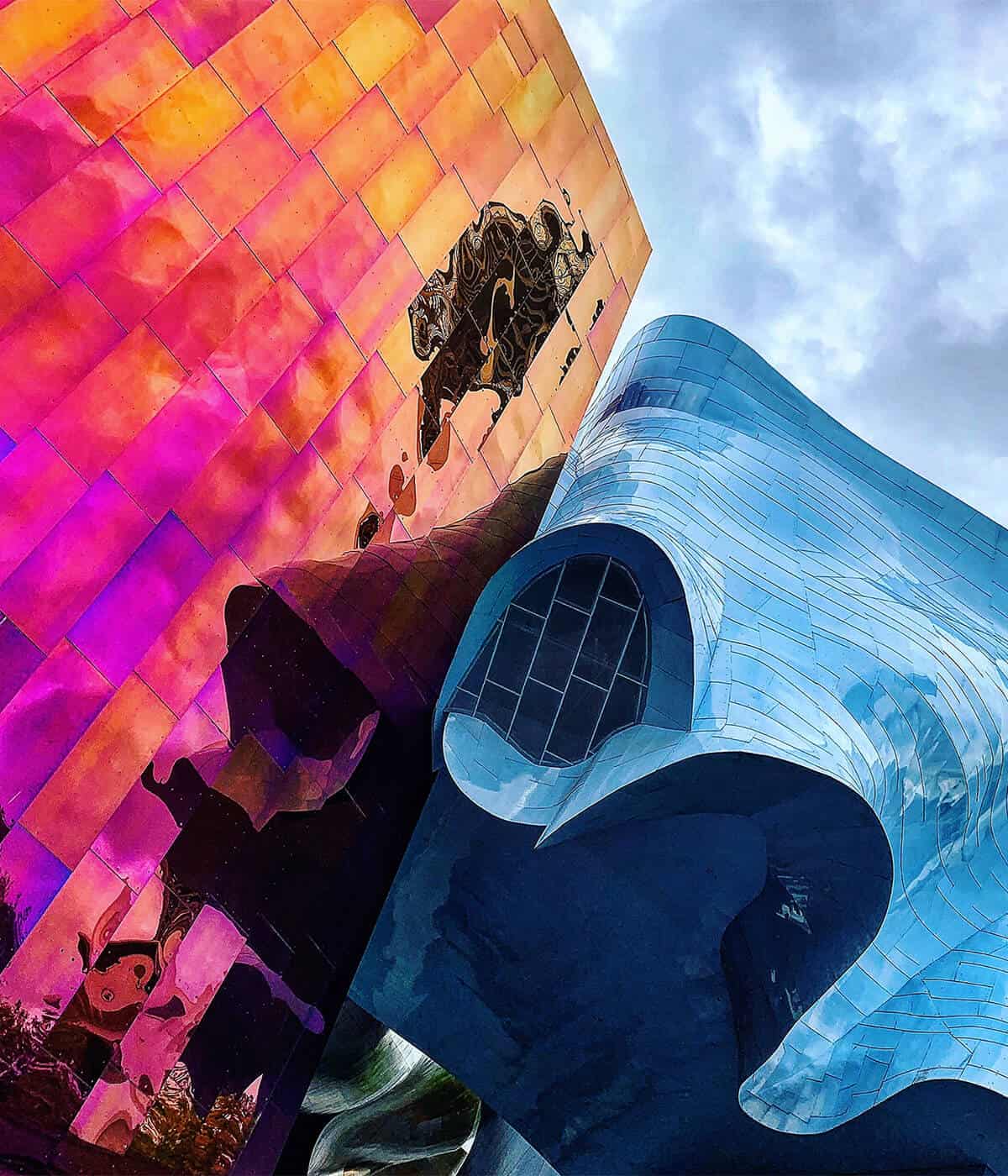

Steve’s approach to complex facade engineering crystallized during a pivotal meeting with Seattle’s Head of Code Review, for what would become his first major iconic project: Experience Music Project, now MoPOP. When questioned about his experience with unprecedented structural challenges, a partner from the superstructure engineering firm spoke first: “Nobody has experience in this kind of work – this is the first one in the world.” Steve’s response became his career philosophy: “If it can be done, we will figure out how to do it.”

This mindset would prove essential as Steve and his team tackled increasingly ambitious projects that pushed the boundaries of what was structurally possible.

The Human Side of Engineering Excellence

What sets Steve’s career apart isn’t just the technical innovation – it’s the relationships and principles that guided every project. His unwavering commitment to engineering integrity became widely respected within the industry. While other engineers might sign off on work as “complete and in conformance” to meet deadlines, Steve maintained his standards, describing work as “substantially complete” when that was the honest assessment.

This principled approach sometimes led to memorable moments, like conducting building inspections 80 feet above a monorail, architectural spelunking through vast cave-like spaces between building shells and metal skins. But it always earned respect and built lasting professional relationships.

Perhaps the most endearing example came during a chance sidewalk encounter with Frank Gehry. Steve’s wife, wearing a contractor’s badge, looked the famous architect in the eyes and asked, “So what is this thing anyway?” After a moment of confusion, Gehry recognized her badge, grinned and gently punched her shoulder saying, “Oh you!” As a partner from Gehry’s office later laughed, “That’s more physical contact than I’ve had with Frank in the last 10 years!”

Engineering the Impossible

Throughout his career, Steve’s team consistently found solutions for challenges that had never been attempted before. Whether it was creating structural systems from materials not traditionally used that way, developing entirely new approaches to eliminate costly conventional frameworks or writing custom structural design codes that passed review without comment, the philosophy remained constant: if it can be done, they would figure out how to do it.

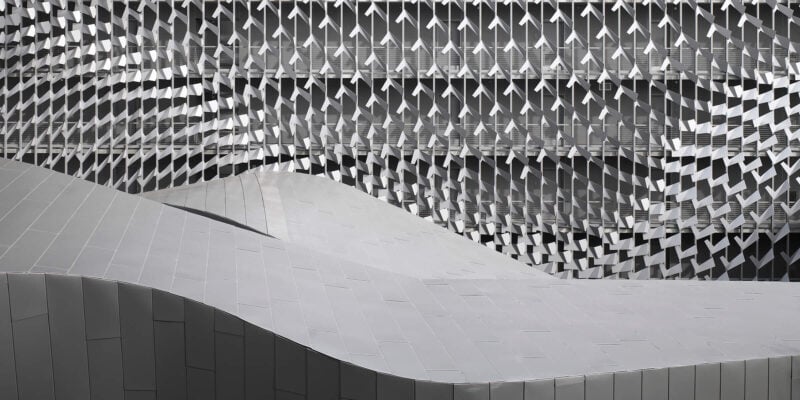

The de Young Museum of Art in San Francisco exemplifies this approach perfectly. Set in Golden Gate Park, one of the world’s most beautiful urban green spaces, the project required groundbreaking structural solutions. According to the American Copper Association, it marked the first time during the modern building codes era that anyone had used cold-formed copper “Z” purlins as structural joists. The building also features extruded bronze wind/seismic girts supporting the wall panels. Steve’s team wrote a complete structural design code for copper and submitted it with their calculations – 2,100 pages in total – as part of the code review package. It passed “without comment,” and the contractor pulled the permit for the facade after just three weeks.

Even when faced with the truly unforeseeable – like a floating casino settling on top of a building during Hurricane Katrina – Steve maintained his perspective and humor. As he told colleagues during a conference call while watching the news footage, “We consider a lot of weird load cases when we design these things, but I really don’t think anyone can blame us for not anticipating this one.”

The Power of Partnership

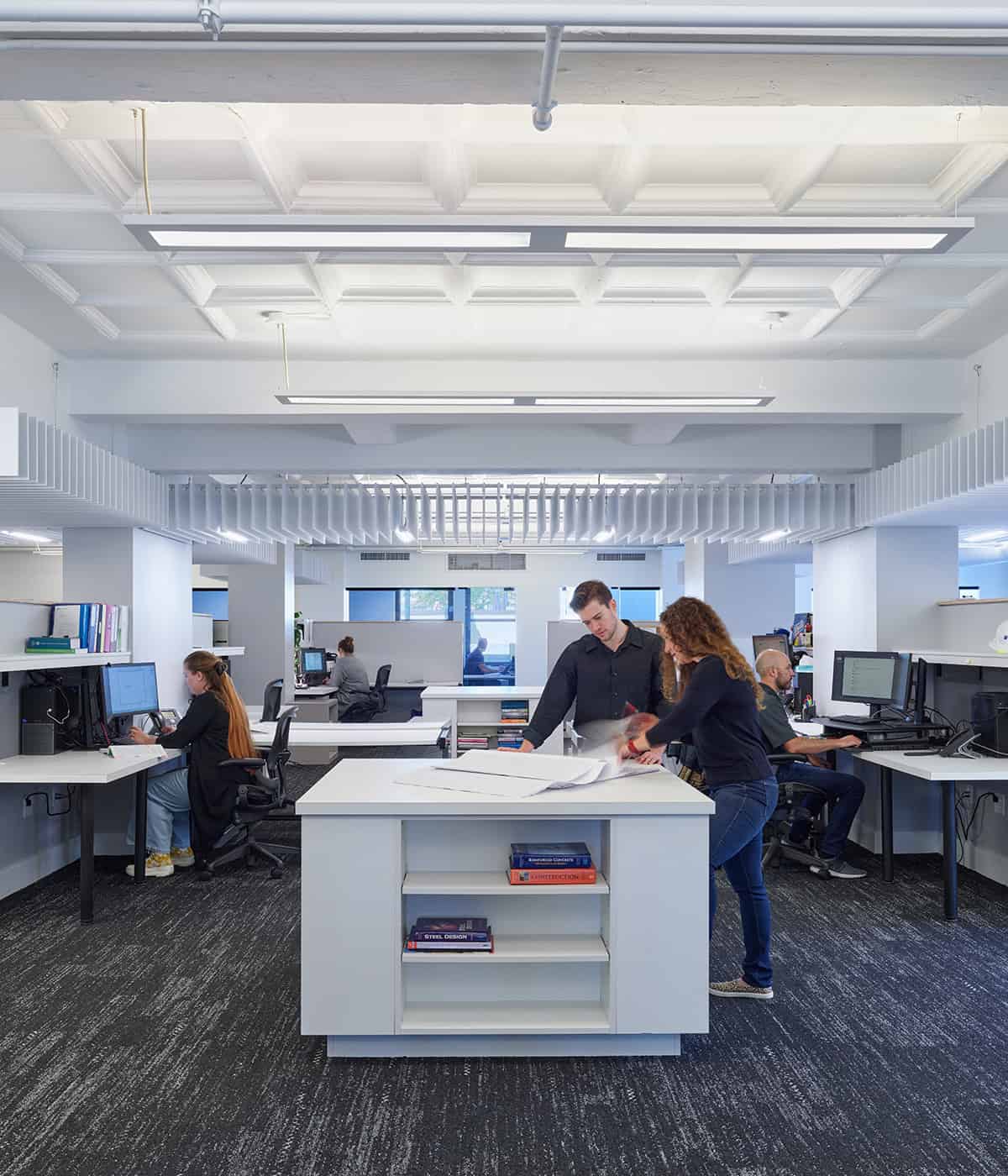

Throughout his career, Steve emphasizes that none of these achievements were solo efforts. “I didn’t do all of this,” he reflects. “These are the accomplishments of a number of engineers over the last 30 years – engineers who are smarter than I am. Without Darcey Schumacher, Jeff Denton, Molly Parisien, Alex Trujillo, and before them Rob Rampetsreiter, Reverend Tom North, and others, none of this gets done. It has always been a team effort.”

Full Circle

The ultimate validation of Steve’s career came from an unexpected source: his oldest daughter, an architectural engineering student at KU. In her design studio, she received a list of 15 iconic buildings to research and present. Two buildings her father had worked on made the list: the de Young Museum and MoPOP. Using personal photos, memorabilia and videos Steve provided – including footage where her mother appears in the VIP section at the MoPOP’s grand opening – she earned an “A” on her presentation.

As Steve prepares for retirement, he’ll complete his work on the Air Force Academy Cadet Chapel, bringing his career full circle to the building that started it all. It’s a fitting capstone to a career defined by the belief that if something can be done, the right team will figure out how to do it.

Never discount childish bravado – sometimes it leads to engineering the extraordinary.

Explore our façade engineering portfolio

From cultural landmarks to complex custom facades, see how our team transforms design challenges into structural solutions that stand the test of time.