When I graduated with my master’s degree in civil engineering, one of the first things I did was send a copy of my thesis to my grandpa, Edward H. Liebold. You might say he was one of the forces behind engineering my future and helping me build a concrete idea of what I wanted to do with my life. Incidentally, he also instilled in me a very deep appreciation for puns…

Some of my earliest memories of my grandpa involve me, my brother, and my mom riding the Metra to downtown Chicago on summer days to visit him during his lunch break. He would meet us at the train station, and we’d walk along the Chicago River as he shared his love for buildings and Chicago with us.

I credit him with being an important influence in my road to becoming a civil/structural engineer, but the older I get, the more I realize I really have no idea what he actually did.

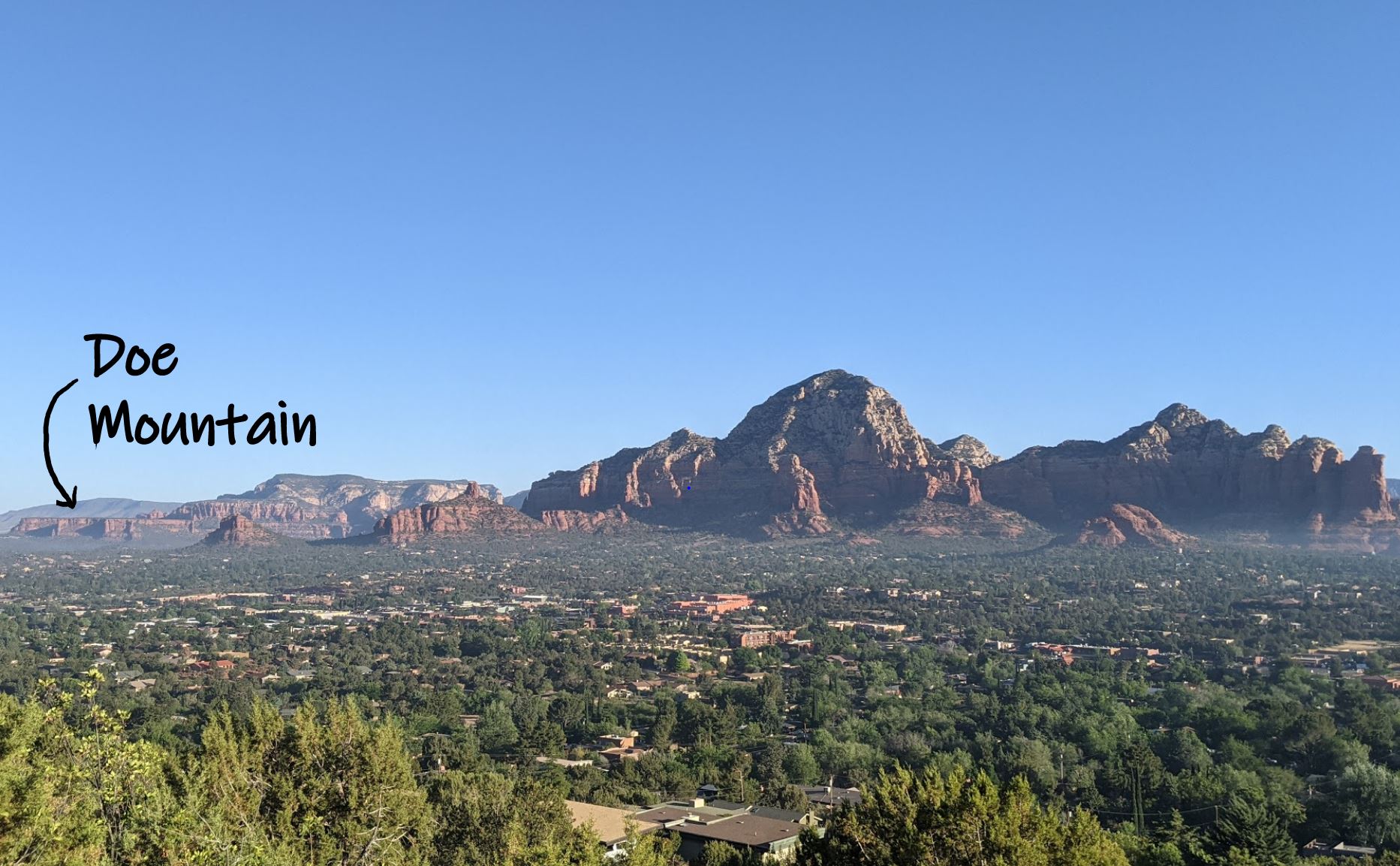

A few years ago, my grandma came across a series of letters from my grandpa, written during his service in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) in 1956. The letters detail one of his assignments: leading a topographic survey crew and setting a triangulation station at a desert mountain near Sedona, AZ. One of the 65 year-old letters contains a pencil rubbing of the USACE survey mark for Doe Mountain.

Questions flooded my mind.

My grandpa? Heading up the crew who mapped the topography that probably set the groundwork for today’s maps? And he himself physically setting the USACE survey mark? What equipment did they use? How long did it take? What was the documentation process for mapping the mountain? How did he determine where to set the survey mark? What challenges did they encounter working in the remote desert?

He passed in 2013 – only a year after I graduated and started working – so I will never get to ask him those questions. Not those, or the dozen others I’ve wondered as I’ve progressed in my career. Questions you don’t really know to ask when you’re in school and can only really conceive after you’ve learned the intricacies of the industry. Language you can only speak and topics you can only comprehend after some years of experience.

Although I’ll never get to have those discussions, I decided to find out what I could about his career and what we would have talked about.

Last week, my mom, brother, sister, and I made a pilgrimage to Sedona to hike Doe Mountain. During our Route 66 road trip out to the desert, I asked my mom to tell us everything she knew about my grandpa’s engineering career. The conversation confirmed how little I knew, or thought I knew.

I knew he attained his civil engineering degrees from Northwestern University.

What I didn’t know is that he basically fell into the degree program by chance. His high school principal noted he excelled in math and recommended he apply for an engineering scholarship being offered by Northwestern. My mom doesn’t know if engineering had ever even crossed his mind, but he jumped at this opportunity, applied, and was accepted. The five year scholarship program paid for his tuition through an internship every fourth quarter, meaning he graduated with no debt and varied work experience under his belt. Sounds like an amazing deal!

He then went back for his master’s degree while he was working. My mom remembers him coming home from his office downtown and racing off to the university for his night classes for several years. No remote learning back then! Interestingly, I inherited most of his master’s textbooks and notes, plus an original copy of his research paper, “Dynamic Response of Columns,” published in a 1963 edition of the Journal of the Franklin Institute.

I knew he served in the Army.

I didn’t realize that he was part of the Corps of Engineers. His two years of mandatory service was deferred while he was in college. Then, based on his degree and experience, he served as part of the Corps, mainly working on surveying projects out west in California and the deserts of Arizona.

I knew he worked for DeLeuw, Cather & Co. in Chicago until his retirement in 1996.

I had no idea that DeLeuw, Cather & Co. (later acquired by Parson’s Corp.) was a big name in transportation planning and mass transit development. Googling the company brings up dozens of reports and studies on transportation planning, light rail transit, and more for places around the world. At a time that was a golden era for expansion of rail mass transit, DeLeuw, Cather & Co. had their hands in everything from Chicago’s ‘L’ to Boston’s subway system to the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART).

I thought he designed parking garages and bridges.

Although I know he loved buildings and structures, after researching DeLeuw Cather & Co. I now realize his work may have been more rooted in transportation planning. I’ll probably never know his true specialty or preferred projects, but I find it interesting that his work was so varied. He got to do a little of everything – from surveying a mountain, to designing the Elmhurst Hospital parking garage, to inspecting the Peace Bridge between the U.S. and Canada, to being involved with Boston’s subway system and BART.

I knew he loved Chicago.

But I never fully grasped that a piece of him lives on in one of the central arteries to the heart of Chicago: the Blue Line of the ‘L’. My grandpa worked on the Logan Square – Jefferson Park extension out towards O’Hare airport, which was constructed in the late 1960s. My mom recalls tagging along with my grandpa one Saturday to inspect an underground station. Although she doesn’t know the specifics of his involvement, he must have played a significant role because she remembers riding in the lead ‘L’ car with my grandpa on the extension’s inaugural run.

I’m not one to really pursue or get sentimental about family histories, but hearing bits and pieces of my grandpa’s career was incredibly intriguing. I imagine what conversations we would have now and the questions I would ask him about his work and what engineering and construction were like and compare it to what I know. I wonder what things I could have learned from him and his experiences to apply to my own career and present day engineering.

Hiking Doe Mountain was cathartic, in a sense. As we hiked up the rocky, dusty trail, I pictured him and his team setting up and moving survey equipment around the steep mountain slopes. I imagined him riding in the helicopter to bring the survey marker target to the mountain top, as he described in his letter. As we scoured the mountain top searching for the infamous marker, I thought about how he would have set the disc with care, the mountain holding a special significance for him. The name was a constant reminder of his wife waiting for him back in Chicago – his Dolores, or his “Do,” as was his nickname for her.

We were unable to locate the survey marker (it turns out Doe Mountain is a bit more of a big, flat mesa than a mountain peak), but I haven’t given up. I hope to contact the Corps and get latitude and longitude information plus any of my grandpa’s notes regarding the marker placement and make the trip again. With all the open ended questions I have, this feels like one door I might be able to close.

As thankful as I am for the new information I learned regarding my grandpa, I’ve learned something much more important: ask the questions. You may not even know what questions to ask right now, but just prompt the conversation. Our elders, from grandparents to neighbors, have so much to tell. They’ve left their fingerprints on more than you realize and have experiences you may not even be able to fathom. You might not truly appreciate their stories or insights today, but get them now, and one day you’ll have the experience and perspective that leads to appreciation.

One day you’ll be grateful you sought them out and asked.

There are no comments.